Regenerating heritage at Melbourne's Rialto Towers

- James Lesh

- Jul 10, 2015

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 18, 2025

The Rialto precinct in Melbourne is undergoing another facelift in the coming months. The Age reported last week that at the corner of Collins and King streets a new wraparound 5-story glass and steel office block would soon be built, adjoining the Rialto Towers. As this part of the Melbourne CBD has been a research interest of mine for a while, I’ve been following this development with interest. The commentary was accepting of the proposal. Fronting more of the Rialto Towers onto King Street is part of the renewal of the area.

As a Melburnian born in the 1980s, I grew up with the Rialto Towers as a sign of permanence on the city landscape. I remember visiting the Rialto on school trips and with my family. It was the tallest building in Melbourne. A vantage from which to see ‘this city of suburbs’.

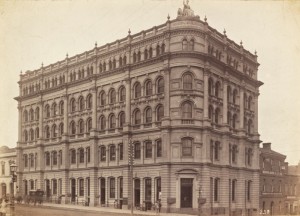

My researching into this area unsettled the permanence that the tower had always held for me. I found much that saddened me in the decade-long dispute over the precinct, especially in how the heritage process failed the site. Until the early 1980s, this was one of the most historic parts of the CBD. A series of “Marvellous Melbourne” buildings lined Collins Street to produce a gorgeous streetscape.

Most of the original buildings were demolished for the Rialto Towers. Although now this precinct is called a ‘heritage success story’, this is, arguably, simply because some of the buildings remain in place and were beautifully restored. This was not the desire of the developer, which sought to demolish all the old buildings to build the tower directly onto Collins Street. Rather, it was a forced compromise after 10 years of dispute and various proposals (including for a casino). The Victorian Planning Minister of the time approved the Rialto Towers without taking the final plan to the independent Historic Buildings Preservation Council (now Heritage Council of Victoria) as mandated. And so approval was given before a financial instrument over the site expired.

Thousands of Melburnians protested their disenfranchisement in the heritage process. Professor of Architecture F.W. Ledger surmised, ‘future generations will conclude that lip-service only was paid by this generation to historic building preservation’. Professor Norman Day thought the development, ‘another case of rape’. Another architect implied the destruction to the city caused by this development paralleled that inflicted by the Nazis on European cities.

Yet a couple of years later the new tower sung ‘Hello Melbourne’. The politics of the heritage conflict had been seemingly extinguished. There was no heritage in sight. The Rialto Towers had become a naturalised part of the city. The Melbourne that I remember from growing up.

The 1970s-80s conflict over the Rialto has been largely forgotten. When new development proposals emerge, it simply provides an opportunity to share sepia tinted nostalgic photographs of ‘buildings lost’.

At these moments, I think it is useful to revisit the politics of heritage too. The loss of the Robb’s Building for the Rialto Towers was unnecessary. A tower that preserved Robb’s in some form could have been built. The forecourt that replaced Robb’s, which is now being built upon with a new wraparound, was part of the compromise to provide the city with an open space to offset the (heritage) impacts of the tower. Now this open space will be built upon as well. These aspects are worth reflecting upon as a reminder of issues that too often emerge in the heritage planning process.

Either way, we can watch a video flyover of the proposed wraparound development. Might I say, a building fitting to the Rialto Towers.